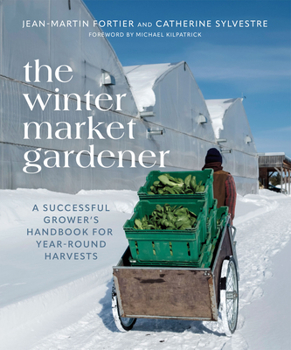

Jean-Martin Fortier is one of the rock stars of small-scale organic vegetable farming, and he has been a popular speaker at our VABF conferences. His book, The Market Gardener: A Successful Grower’s Handbook for Small-Scale Organic Farming, was published in English by New Society Publishers in 2014. It has been available in French since 2012, and has sold over 15,000 copies. Jean-Martin and his wife, Maude-Hélène Desroches, set up an impressively productive, tiny bio-intensive vegetable farm in Southern Quebec, Canada. The farm uses low-tech and manual farming methods (i.e., no tractors), and the farmers found some unusual and successful high-yielding techniques.

The farm is just 1.5 acres, arranged as 10 plots each of 16 raised beds 30” x 100’ long. The paths are 18” wide. The garden plots surround the building, which was a rabbit barn before the farmers converted half of it into their house and half into a packing and storage shed. Their planning is a wonder of considered efficiency and function. I hear it’s also beautiful.

This book will be an inspiration to all those hoping to start in small-scale vegetable farming but are lacking land and money. If you can gather the money to buy a small amount of land (or find some to rent), this book will provide you some of the expertise to make your very small vegetable farm successful, without tractors or employees. Neither Jean-Martin nor I would claim it will be easy, but this book shows that it is possible, given hard work and smart work. So, don’t believe those who say it can’t be done. The tips from this book will ease your way, once you have served an apprenticeship on another farm.

Their small farm is called Les Jardins de la Grelinette, which translates as Broadfork Gardens, giving you a clue to one of the tools they value. In many ways, Jean-Martin is in the school of Eliot Coleman, producing top-notch vegetables and books from a small piece of land with only a small workforce. Even the drawings remind me of those in Eliot’s books. Biologically intensive production can feed the world, as well as provide a decent living for farmers. Attention to detail is required, as there is little slack for things to go very wrong.

They run a 120 share CSA for a 21-week season and sell at two farmers’ markets for 20 weeks. They grow a ponderous quantity of mesclun (salad mix)! They even sell it wholesale. Jean‑Martin and Maude-Hélène studied the value of all the crops they grew, comparing sales with labor and other costs, including the amount of land used and the length of time that crop occupied the space. They provide a table of their results, assigning profitability as high, medium, or low. A quick glance shows you why 35 beds of their 160 bed total grow mesclun – number 2 in sales rank, despite being only number 19 in revenue/bed. This is because salad mix only takes 45 days in the bed, and then another crop is grown. This book deftly illustrates the importance of farming to meet your goals and to fit your resources. My climate is very different from Quebec. I’m providing 100 people for a 52-week season. We don’t want 300 pounds of salad mix each week! We do want white potatoes, sweet potatoes, carrots, and winter squash to feed us all winter – crops that have no place at La Grelinette.

And yet I find more similarities than differences. We both want high-yielding, efficient farms that take care of the planet, the soil, and the workers, as well as the diners. We value quality, freshness, and flavor. We do season-extension to get early crops in spring. When novelty is important, we grow several varieties of a crop.

The start-up costs at La Grelinette ($39,000) include a 25’ x 100’ greenhouse, two 15’ x 100’ hoophouses, a walk-behind rototiller, and several big accessories, a cold room, irrigation system, furnace (remember they are in Quebec!), a flame weeder, various carts, barrows and hand tools, electric fencing, row cover, insect netting, and tarps. Jean-Martin sets out all the costs, all the revenue from each crop – valuable solid information for newbies or improvers alike.

I came away from this book with several ideas to consider further. Jean-Martin recommends a rotary harrow rather than a rototiller. It has vertical axes and horizontally spinning tines, and stirs the top layers of soil without inversion, being kinder to the soil structure. It comes with a following steel mesh roller, which helps create a good seed-bed. Earth Tools BCS in Kentucky sell Rinaldi power harrows that fit the bigger BCS walk-behind tractors. The Berta plow is another BCS accessory that Jean-Martin favors, in his case for moving soil from the paths up onto the raised beds. I think we could really use one of those too.

Broadforks and wheel-hoes are already in our tool collection, but the use of opaque impermeable tarps to cover garden beds short-term between one vegetable crop and the next is really new to me. These tarps are sold as silage/bunker/pit covers, and are 6mm black, UV-inhibited polyethylene. Weeds germinate under the plastic, where it is warm and moist, and then they die for lack of light. Earthworms are happy. The tarps can be cut to the width of one bed, and rolled after their 2-4 weeks of use. This could be a useful alternative when there is not enough time to grow a round of buckwheat cover crop (or it is too cold for buckwheat, or your tiller is in the shop). Weed pressure on following crops is also reduced. Tarps can be used to incorporate a flail-mowed cover crop as an alternative to using a tiller.

At Twin Oaks, our gardens are in many ways like a CSA with one big box for the whole community, but in other ways we are more like a self-sufficient homestead – we try to keep our bought-in inputs to a minimum, so producing our own compost and growing cover crops for increasing soil nutrients are valuable to us. They do not fit so well for a micro-farm in the cash economy. For La Grelinette, it is better to buy in compost and poultry manure and keep using all the land to grow more vegetables.

The book includes tables of which crops go where, when to plant in the greenhouse and outdoors, pest control options, and lists of what to grow. The appendices include brief bios of 25 crops, and a short list of the crops they don’t grow and why (i.e., potatoes, sweet corn, winter squash, celery, and asparagus).

Jean-Martin Fortier.

Photo New Society Publishers

Jean-Martin is obviously very particular about running their farm as efficiently as possible, but don’t make the mistake of thinking he must be a grim workaholic! He is very funny with his iconoclastic sidebars. “Crop rotation is an excellent practice . . . to ignore.” (He is addressing new farmers who will likely find plans need to change to improve productivity. He doesn’t want slavish dedication to a crop rotation to prevent someone seizing on a better idea.) His paragraph on the hazards of inexperienced workers with insufficient training and oversight was so good I read it out to my crew. We have never had leeks sliced off at the surface or pea plants pulled up as harvest methods, but we have had carrot seedlings pruned to a uniform height of an inch, rather than thinned to a one inch spacing! If you get a chance to hear Jean-Martin speak, don’t pass it up.

This book is a delight and an inspiration, well worth the cover price. 224 pages, black and white drawings, 8.5” x 8.5”, $24.95. ISBN 978-0-86571-765-7, New Society Publishers.