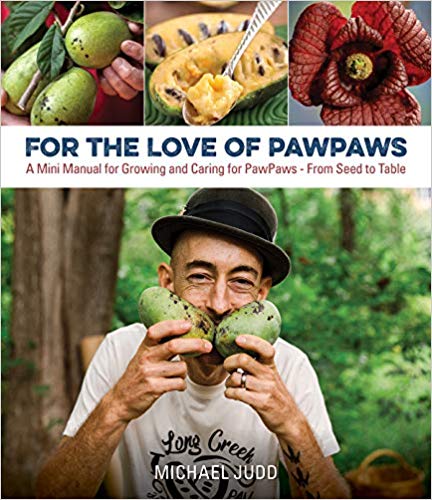

This wonderful new book is inspiring and appetizing, practical and beautiful. About 150 pages of glorious photos, technical details, mouthwatering recipes, and anything else you might need to start growing pawpaws or to make better use of wild pawpaws on neglected trees nearby. Here you can learn the reasons to plant named cultivars that have been selected for size, flavor, and high yields.

Michael Judd, his wife Ashley and son Wyatt live at Long Creek Homestead in a round house on a homestead in the Maryland Appalachian foothills, where they grow many food trees and other fruits, and hold an annual Pawpaw Festival each September (more on that at the end of this review).

Pawpaws are related to custard apples and cherimoya, in the sugar apple family, and yet they grow in the temperate zone, having moved north as Ice Age glaciers receded. Flavors of mango, banana and pineapple come from this creamy fruit. But if you don’t know what you’re doing and you let them get bruised, or you pick them under-ripe, you can end up with a bitter taste in your mouth, or a bellyache. So get this book!

Learn how to spot wild pawpaws in a forest edge or along a river bank. They need full sun to develop good flavor, although the trees will grow in the shade. If you want to grow your own, you can of course grow them from wild seeds (that you keep damp and plant right after eating the fruit). Michael points out the four key elements of successful pawpaw production:

- moisture (minimum of 32” (81 cm) annual rainfall or access to continuous soil moisture);

- well-drained soil, preferably fertile;

- warm humid summers with 160 frost-free days;

- cold winters including some freezing temperatures and at least 400 chill hours.

USDA Winter-hardiness zones 5-9 are most-suited. If these factors are addressed, the pawpaw can be an easy-care fruit tree. We have all those factors in our area of central Virginia, and we have wild trees along the South Anna river. We also have cultivated varieties planted near our houses. Given the right conditions, pawpaw trees grow to an attractive 25 ft (7.6 m) pyramid shape, and can bear 50 lbs (23 k) of fruit each year.

It’s best to have two or more genetically different trees close together, for good cross-pollination and heavy fruit set. Individual flowers cannot pollinate themselves, and although each tree can self-pollinate, the yield might not be large. The unusual purple-brown flowers are fairly inconspicuous.

If you have only eaten wild pawpaws, you’ll be amazed at the cultivated ones – much bigger, with a more balanced sweet flavor, delicious aroma and smooth texture. Michael offers advice on choosing a variety and choosing and planting potted seedlings. He introduces us to Neal Peterson, who he calls the Mahatma Pawpaw. Neal has created most of the best pawpaw cultivars. I profiled his work here.

Factors to consider include when the fruit ripens and whether all fruits ripen within a small window; whether the fruit softens quickly; whether the skin is thin (undesirable if you are selling or attempting to store the fruit); whether they tend to split in rainy weather; whether they need a lot of fruit thinning to preserve the health of the tree; how big the fruit is (4-6 oz (114-170 g)? 8oz (227 g)? 16 oz(454 g)?) ; the seed:pulp ratio (some big fruits have huge seeds – an ideal range is only 4-8% seeds). Michael offers profiles of the seven Peterson cultivars, the three Kentucky State University cultivars and Jerry Lehman’s two named cultivars. For the wannabe-grower in a hurry, there is a summary of the best cultivars for several factors, and for the person who has no time to read or experiment, Michael suggests sticking with the long-proven wild-sourced cultivars Overleese, Sunflower, PA Golden and NC-1.

Factors to consider include when the fruit ripens and whether all fruits ripen within a small window; whether the fruit softens quickly; whether the skin is thin (undesirable if you are selling or attempting to store the fruit); whether they tend to split in rainy weather; whether they need a lot of fruit thinning to preserve the health of the tree; how big the fruit is (4-6 oz (114-170 g)? 8oz (227 g)? 16 oz(454 g)?) ; the seed:pulp ratio (some big fruits have huge seeds – an ideal range is only 4-8% seeds). Michael offers profiles of the seven Peterson cultivars, the three Kentucky State University cultivars and Jerry Lehman’s two named cultivars. For the wannabe-grower in a hurry, there is a summary of the best cultivars for several factors, and for the person who has no time to read or experiment, Michael suggests sticking with the long-proven wild-sourced cultivars Overleese, Sunflower, PA Golden and NC-1.

The chapters on growing the trees includes collecting seeds, germinating them, planting, grafting, choosing rootstock and the importance of soil fungi. Read about companion planting with nitrogen-fixing plants (such as lead plant, false indigo, black locust, which will need cutting back later) and soil-covering “mulch” plants (such as comfrey, yarrow, lemon balm, fuki, white clover). The tree-care chapter includes fruit thinning, and pruning (avoid climbing these brittle trees by keeping them 8 ft (2.4 m) tall).

I was thrilled to learn that the zebra swallowtail butterfly has a single host – the pawpaw! We have these butterflies (in small numbers) and I didn’t know much about them. The caterpillars do not do significant damage to the leaves of grown trees, and the acetogenins from the leaves make the insect unpalatable to predators.

Harvesting is both art and science. Under-ripe pawpaws can lead to belly-ache. Mishandling pawpaws can quickly lead to poor results. Windfalls that have lain on the ground for several days will likely be funky in smell and bitter in taste – don’t let your first experience of pawpaw be like this! The ideal is to hand-pick ripe fruit, and as the transition from rock-hard unripe pawpaws to ripe is very sudden, you’ll end up checking the same fruits more than once. Some cultivars change color, others don’t. Check daily! Ripening can finish later if they have begun ripening before you pick. The harvest period lasts 2-4 weeks (July in the Deep South, late August and early September in central Virginia, October in the Great Lakes region).

Be very gentle in handling these delicate fruits. Eat within 72 hours of picking or refrigerate (for 1-3 weeks, with the longer period being in a large cooler with a big air volume) Pawpaws exude large quantities of ethylene when ripening. This colorless, odorless gas causes other crops in the same storage space to ripen more, or to sprout, or in the case of carrots, to taste bitter. Alternatively, pulp and freeze (or freeze and pulp). This is one of the places where you learn time- and money-saving secrets – freeze the fruits whole, remove from the freezer after 12 hours, warm them for half an hour, then peel as if they were potatoes, pry them open and pop the seeds out cleanly. Put the frozen chunks back into the freezer until you have more time. There are tips about keeping the yellow color, and which food mills and sauce-makers can pulp pawpaws.

There’s info on the nutritional content of pawpaws: 3.5 oz (100 g) provides 80 calories, including 1.2 g of protein and fat, and all of the essential amino acids.

The next section of the book is recipes and mouth-watering photos. (Cheesecake! Ice-cream!) First are the recommendations on eating pawpaws fresh off the tree, and in other ways raw. Next are the cautions about baking with flour which can mask the more subtle flavors and leave something that could be mistaken for banana pie or butterscotch tart. There are vital guidelines on how to use pawpaw pulp in recipes, and what not to do (do not boil or dry the fruit). Many pawpaw recipes are high in cream, butter and sugar, which you might relish. However, here are also some recipes that are healthier, including some vegan recipes. There’s also a simple recipe for unsweetened pawpaw jam, which they cook on a rocket stove, and one for pawpaw butter that includes some sugar and some bourbon. And beer, mead and kombucha.

The first appendix is “Pawpaws and Permaculture” – here’s one of the special things I like about this book. First we learn about this particular tree crop, and bit by bit we see practices we associate with permaculture – the swales, mulches, companion plants. It all makes sense. Here is an explanation for those of us who are not filled with religious zeal at every awed utterance of the word “permaculture”. I’m not the type to believe a theory then fit my practice into that theory. I’d rather practice, observe, learn about options, choose from the most likely to succeed, evaluate, tweak, do a small experiment with a different method, and so on. Here’s “Permaculture for the Rest of Us.”

I also got insight into what permaculturists mean when they talk of “Food Forests”. They don’t actually mean acres of food trees. They mean small clumps of trees within a lawn. Agroforestry is the name for the type of farming that includes trees as windbreaks and crops, and pawpaws are a good candidate for inclusion. Goats don’t eat pawpaw trees! In this part of the book, the place for pawpaws in Hügelkultur beds (piles of wood covered in soil); greywater berms (shallow trenches funneling sink water into the landscape; and rain gardens (areas that store rainwater in the soil to irrigate plants) is explored.

For those venturing into commercial pawpaw growing and marketing, there is a profile of Deep Run Pawpaw Orchard in Maryland, where trees are 8 ft (2.4 m) apart in rows 15 ft apart (4.6 m), and produce 6,000 lbs (2.7 metric tons) annually. Their best varieties are Shenandoah, Allegheny, Susquehanna and PA Golden, and grafting onto wild rootstock has given them better drought tolerance. They have tips on commercial-scale pruning, thinning and fertilizing.

I have one little quibble with this book, which is that it would have benefited from tighter editing in some places. It’s not at all verbose or convoluted, but sometimes a piece of info has become detached from its colleagues, and occasionally it gets repeated. But all the info here is good, and actionable. And if you don’t read the whole book at one sitting, as I did, it won’t even be a problem!

After you’ve enjoyed the book, and maybe before you go shopping, if you are anywhere nearby, book in for the annual Pawpaw Festival at Long Creek Homestead near Frederick, Maryland. The 4th Festival is September 21st, 2019 12-5 pm. They also have set open days between March and June, and in September and October. No! No! don’t just show up at their home at some random time of your choosing! See their website www.ecologiadesign.com

Michael Judd, Published August 2019 by Ecologia, Distributed by Chelsea Green Publishing, ISBN 978-0-578-48874-5.

By Pam Dawling