-Formidable Vegetable.

Permaculture is a holistic design system based on observing nature. Its methods ensure that the output of your system far outweighs its inputs. As farmers, we want yields that increase year after year without our expenses going up. One way that this can be achieved, whether in a large-scale farm or a home garden, is by composting.

Â

Why Compost?

An abundant yield is the result of many things: seed variety, climate, and pest/disease resilience. Here in Virginia, we are blessed with more than 40 inches of rain a year and a fair amount of sun. So, once we have selected our seeds, an abundant yield all comes down to soil fertility.

For the last 100 years or so, American farms have used many methods to work the soil: We, spray, lyme, amend and the list goes on. But which of these methods build fertile soil?

Soil scientist, Dr. Elaine Ingham is famous for saying, “All the mineral nutrients your plants need are already in the soil.”

How is this possible when some of our crops die?

The answer may lie, not so much in the presence of mineral nutrients in our soils, such as (N) nitrogen, (P) phosphorus and (K) potassium, but in their bioavailability to the plants. Let’s take the case of (N) nitrogen, for instance.

Air is composed of mainly of 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen & 1% mixed gasses. But this atmospheric nitrogen cannot be used by plants without the presence of “nitrogen-fixing” bacteria. These bacteria, mainly found in legumes such as our peas, beans, and cover crops, certain trees (alder, locusts, redbuds, etc.,) and bushes (goumi berry, sea buckthorn, soapberry, etc.,) are unique in that they change N2 into ammonia (NH4) or nitrate (N03). Depending on what you are growing, your plant will like either of these “nitrified forms.” Blueberries, for instance, love the ammonia form, and most other vegetable crops, especially grasses like corn prefer nitrate.

Another feature of healthy soils is the presence of mycorrhyzal fungi which extend the roots of our plants. Both annuals and perennials and increase their ability to absorb water and nutrients necessary for their growth when they partner with these fungi. In one study of the relationship between these beneficial fungi and plants, an electron microscope captured a fungal hypha (thread) strangling a predatory nematode (Lowenfels, & Lewis, “Teaming with Microbes”). Mycorrhizal fungi essentially protect the plant from its enemies. Once established in the soil, their hyphal threads can stretch from miles on end. They can potentially send messages from one side of your field to the other. This is why mycorrhyzal fungi are also called the “Internet of the Soil.”

Another feature of healthy soils is the presence of mycorrhyzal fungi which extend the roots of our plants. Both annuals and perennials and increase their ability to absorb water and nutrients necessary for their growth when they partner with these fungi. In one study of the relationship between these beneficial fungi and plants, an electron microscope captured a fungal hypha (thread) strangling a predatory nematode (Lowenfels, & Lewis, “Teaming with Microbes”). Mycorrhizal fungi essentially protect the plant from its enemies. Once established in the soil, their hyphal threads can stretch from miles on end. They can potentially send messages from one side of your field to the other. This is why mycorrhyzal fungi are also called the “Internet of the Soil.”

As permaculture guru, Geoff Lawton likes to say, “We don’t feed the soil. We feed the life in the soil.”

And that is one of the big reasons to compost:Â To cultivate the ecosystems below ground, that are fueling the ecosystems we grow above ground.

Â

(3) Three Composting Methods

How do we make compost? There are many different ways to create compost, but I would like to zero-in on (3) three basic methods that I use and am most familiar with:

-

- An Outdoor Composting Bin or Pile

Perhaps the most common composting system which is easy to establish and maintain is a large heap that is layered with brown matter (carbon), decomposing greens (nitrogen). The other three ingredients necessary are:

- The pile must be damp but not so soggy that it turns anaerobic (no air). You will know that this is the case if your pile becomes stinky.

- The pile must get good oxygen. You can achieve this by regularly turning the entire heap so that what was previously on the bottom comes to the top.

- The pile heats up to about 150F – 160F to be effective.

-

-

- Hot Composting (Compost in 18 Days)

-

The Berkley Method was developed by Dr. Robert Raabe of UC Berkley. It requires a mere 3-by-3-foot pile of brown matter and any material which is cut green. Brown matter can even come in the form of shredded newspaper and green matter can be made of grass clippings or kitchen scraps. This kind of pile is suitable especially for the home garden. There are two things important to note about this method:

- The ratio of (C: N) is (30:1). That is a very high carbon and a very low nitrogen requirement.

- You must turn this heap daily or every other day to achieve compost in 14-28 days. The more frequently you turn it, the sooner you get your compost.

This 18-Day Hot Composting Method is similar to the Berkley Method, but results in a richer type of compost (as manure is also added). This method also ensures that no elements are lost as gas emissions and that your compost heap does not burn off and decrease in size as the days go by.

Geoff Lawton’s formula is similar in its C: N ratio, but he does give options for the types of carbon and nitrogen one can use and encourages you to build a more complex compost than simply brown cutting and green cuttings. You can do this by varying the types of browns and greens that you use and adding manure. He also recommends building a 5-by-5-foot pile, instead of a 3-cubic foot one.

These are the two things important to note about this method:

- You must use 1/3 browns + 1/3 manure + 1/3 greens

- Turn the pile the first day, then let it sit for (4) four days. Turn every other day after then, until you hit day 18.

-

-

-

- Cold Composting

-

-

The Cold Composting Method is simply to have an indiscriminate pile dedicated to both browns and greens and just let it sit for 3-6 months until everything is broken down. This is a lazy way of composting. And yet, can be a very effective one if time is not of the essence.

-

- Vermicompost

Â

Â

-

-

- Red Wriggler Worms

-

This is the type of composting we recommend especially for home gardeners because the composting worms or “red wrigglers” (Eisenia foetida) specialize in eating food scraps. Thus, they can breakdown a higher quantity of food waste on a more frequent basis.

The problem with the hot and cold composting methods mentioned above is that once you get a pile started, you cannot add to it, or you will have to start counting your days over. With vermicomposting, you can add your kitchen scraps to your worm bin every day and the worms will eat half their weight!

One flower farmer from Rochelle, VA keeps worms which she inherited from her grandfather, in an old dairy churner. When we last saw her, she intended to aerate the drippings from these worms to make “compost tea.” Here she is feeding her worms.

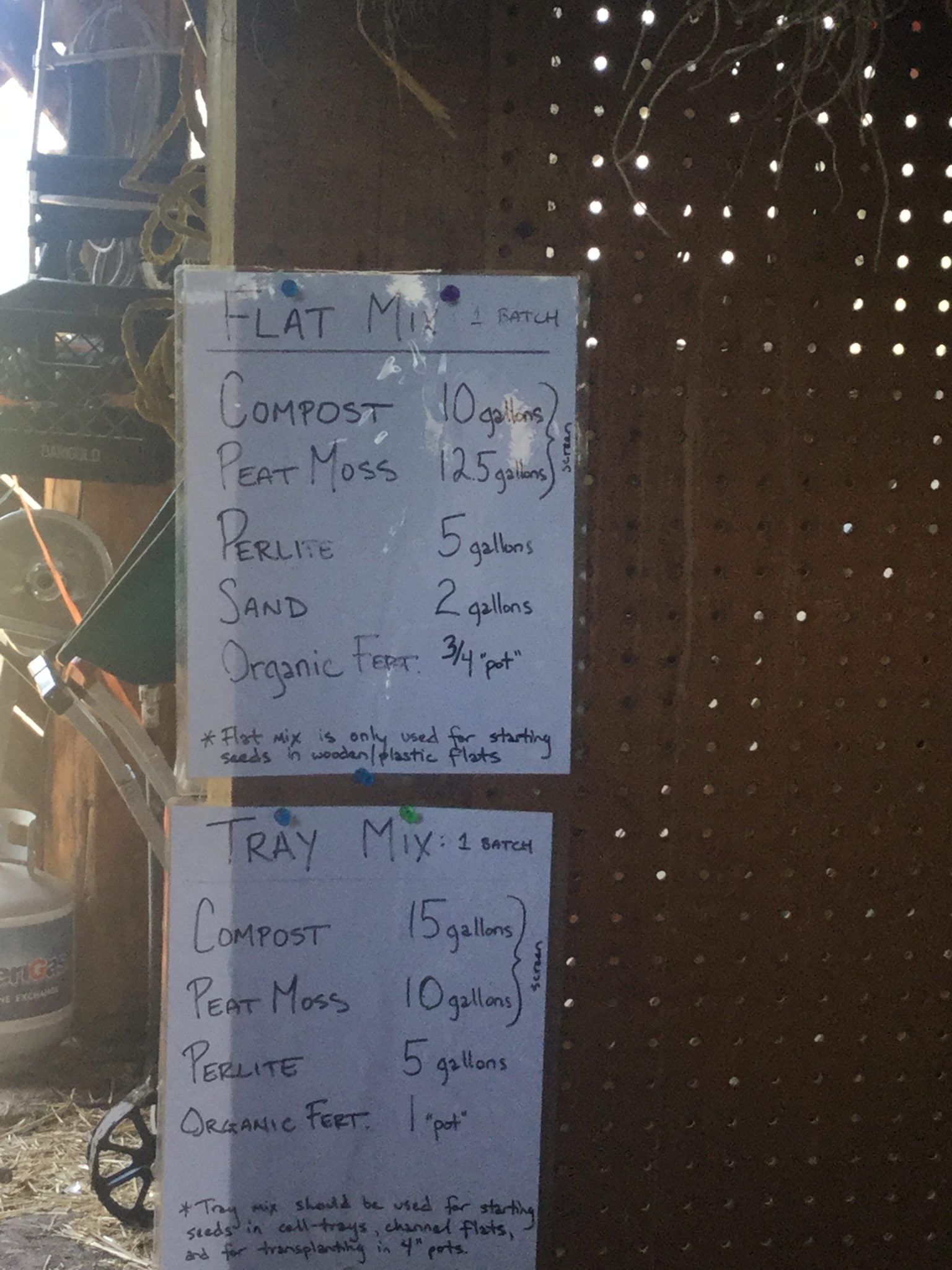

Another farmer we met on a recent visit to Montana, also uses compost tea to build soil and promote crop growth. His worm bin drippings are run into a 50-gallon barrel fitted with a compost tea bubbler which is used to ensure the tea does not turn anaerobic and kill the beneficial micro-organisms which he intends to propagate in the soil. Here is his formula for his seed starting potting mix:

Another farmer we met on a recent visit to Montana, also uses compost tea to build soil and promote crop growth. His worm bin drippings are run into a 50-gallon barrel fitted with a compost tea bubbler which is used to ensure the tea does not turn anaerobic and kill the beneficial micro-organisms which he intends to propagate in the soil. Here is his formula for his seed starting potting mix:

-

-

- Meal Worms

-

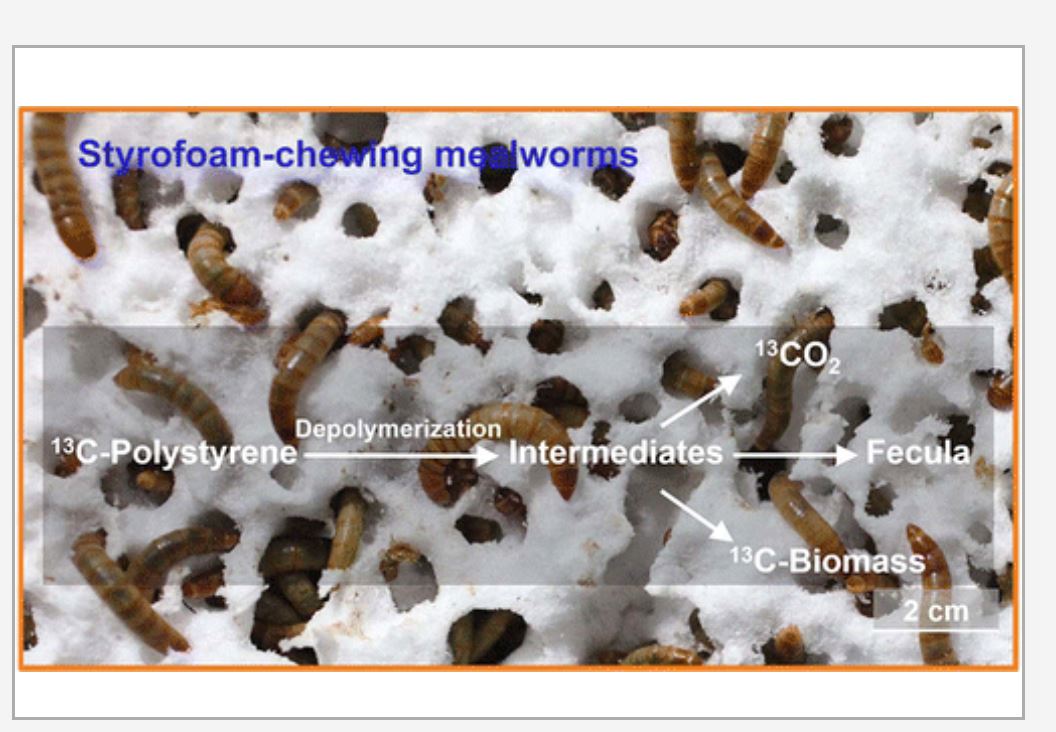

A 2015 Stanford Study revealed that mealworms can effectively biodegrade plastics such as Styrofoam. Mealworms are the larvae of Tenebrio molitor, a species of the “darkling beetle.â€Â Using a separate worm bin for mealworms would help dispose of otherwise, non-biodegradables such as Styrofoam.

-

Bokashi

Bokashi

The final composting method, I would like to talk about is the Bokashi fermentation method. This method was first officially introduced in Japan by Dr. Teruo Higa of Ryukyus University in Okinawa as part of his development of EM or “Effective Micro-organisms.” Many sources believe that its origins lie in traditional Korean Farming Methods.

Bokashi is a way to ferment or pre-digest organic materials that would not normally be included in a vermicomposting bin. Usually, these are citrus (worms do not like citrus), bones, meats, cheese, fats, bread, and pasta. The fermentation process involves adding a small amount of EM-laden bran into an air-tight bin with a spigot. See picture below.

The EM breaks the materials mentioned above and releases an acidic bokashi tea (which you can drain from the spigot of your container). However, this bokashi leachate must be diluted in water before applying to your soil. Once your bin is full and has fermented for (2) two weeks, the remnants are then added and worked into your garden soil where they are decomposed for another (2) two weeks (or more).

The EM breaks the materials mentioned above and releases an acidic bokashi tea (which you can drain from the spigot of your container). However, this bokashi leachate must be diluted in water before applying to your soil. Once your bin is full and has fermented for (2) two weeks, the remnants are then added and worked into your garden soil where they are decomposed for another (2) two weeks (or more).

The main difference between this method and most composting methods is

- It’s anaerobic and you must make sure your bokashi bin is air-tight.

- You need to have a supply of EM to promote this fermentation process or else, you will cultivate the wrong type of bacteria in an air-tight bin.

Currently, we would like to study how to cultivate our bokashi micro-organisms so that we do not need to purchase additional inputs for this fermentation process to work.

Conclusion

I hope that this article will encourage you to keep up your current composting efforts. Perhaps you can do further study and experimentation on what kind of methods work best towards increasing your yields.

If you have any tips that other Virginia farmers can learn from, please hit reply so we can share your advice with others who might benefit from it.

Here’s a video that summarizes the hot composting methods above as used in the deserts of Jordan. It is not much different than composting in Virginia, but it shows that composting can be done even in the desert and ties in well with Pam Dawling’s past book recommendation about “Drought Resiliency.â€

BY: Nicky Schauder