I first learned about Lick Run Farm in Roanoke when our friend Rachel Theo-Maurelli joined my wife and me for dinner one evening this summer. Rachel has worked in urban community gardens in Norfolk (1999 -2007) and Roanoke (2007 to present). During her Roanoke years, she asked me for help with soil test interpretation from time to time. When she described her work at Lick Run Farm where she started this year, it sounded like an inspiring project, and we arranged for me to meet farm owner and coordinator Rick Williams, and farm manager Karen Stretton to learn more.

Lick Run Farm comprises 3.5 acres of mostly-open land in Washington Park, a low-income neighborhood in northwest Roanoke, which USDA has designated a “food desert.â€Â The farm is located about a half mile from the Villages at Lincoln, a large subsidized housing project. When Rick first bought the land in 2010, it presented a tangle of overgrown nursery stock, left over from the Crowell Family Nursery, which closed in 2002. He spent the next several years clearing the land, building a living soil, and establishing annual and perennial food gardens as part of his larger vision. Food production began in the garden near the house in fall of 2012, and has now expanded into a larger hilltop field further from the street.

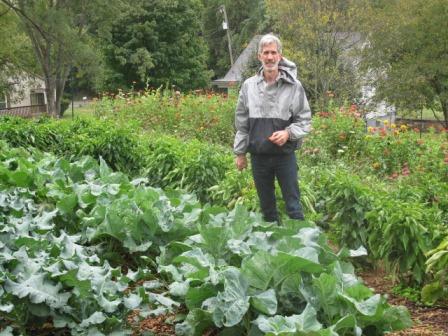

I visited the site on a drizzly day at the beginning of fall 2015, parking by a large, welcoming sign “Lick Run Farm and Community Market†near the Crowell family house. Rachel greeted me from a fenced garden where she was working with several other gardeners, and introduced me to Rick, who showed me around the farm. We climbed a sharp rise behind the street-level garden to a larger field with healthy crops of fall greens, cauliflower and broccoli, brilliant red peppers, flowers, and a bed of peanuts. “We first started gardening here in 2014,†he says, then points out two new fields in a re-seeding cover crop of buckwheat and Japanese millet. “The soil there is good bench land, above the flood plain, and with less shale than the other areas.â€

“We practice low-energy-use, low-tech, biological farming,†Rick notes, “with emphasis on soil health, cover crops, compost, and compost tea.â€Â He summarizes his farming philosophy with a quote from Rudolf Steiner, the early 20th century German scholar who founded the Biodynamic farming movement: “put back what you take and a little more, and nature will provide abundantly.â€Â He is especially enthusiastic about the benefits of cover crops. “When we cut cover crops like rye and leave the top growth in place as mulch, it supercharges the soil. Japanese millet forms a dense mat of roots that leaves the soil so soft, it is beautiful to see.â€Â He plans to establish defined beds and paths, growing cover crops in the beds and mulching paths with wood chips or straw. When the path mulch breaks down, he will hoe it up onto the beds and put fresh mulch in the paths.

Two new fields in self-seeding cover crops of Japanese millet and buckwheat replenishing the soil in preparation for future food production at Lick Run Farm.

Long term plans for Lick Run include permaculture gardens over much of the 3.5 acres, “which I now realize is a lot of land,†Rick adds.  He plans to install a forest garden in the far corner of the land, using the methods of Eric Toensmeier and David Jacke. Another as-yet undeveloped area, the corner lot on 10th street that I passed as I drove up to the house and fenced garden, will go into perennial fruit.

“Development has been at times painfully slow,†Rick notes, adding that all of the money going into this project comes from his day job as a software engineer in process automation. However, he adds that there are benefits to developing slowly. “Nature does not do things overnight; it takes time to build something sustainably.â€

Rick then shows me into the house, the original part of which was built in the 1890s. In the late 1940s, Thomas and Laura Crowell moved here, added front and back sections to the house, and established the nursery business. Rick is currently fixing it up as a living and work space under Roanoke’s “neighborhood commercial†zoning category. “I am making my own home here, in addition to a marketing area, neighborhood meeting space, and facilities for the farm,†Rick explains. “I want to live here, as it does not work as well for comfortable folks to drive in from their safe suburban neighborhood to promote urban farming and economic development.â€

Vision, goals, and unfolding

At the outset in 2010, Rick developed a vision statement. “This isn’t just about farming,†he says. “Our goal is to rebuild an inner city neighborhood. Small scale biological farming is indispensable as an economic base activity that is accessible to everyone, brings money into the neighborhood, and provides work for the neighbors. This is something that everyone will ultimately need to learn,†he notes, adding that industrial scale farming cannot sustainably provide for our food supply long term.

The Lick Run Farm vision begins with combining the free inputs of rain, sun, and healthy soil with labor, seeds, and compost to yield a salable product. The market space on site will become a place where people in the neighborhood will want to gather for social interaction and economic development. Planned activities include cooking classes in which local chefs show residents how to use whatever is in season to make tasty, nutritious, easy-to-prepare meals. “I call this bottom-up gentrification,†Rick says. “The market will generate economic activity including but not limited to good food, and will give neighbors an opportunity to participate and make income in the process.â€

Realizing the part of the vision that entails community involvement and neighbors working at the farm thus Rick observes that this reality is evolving gradually. Thus far, about eight people from the neighborhood come to the farm regularly to buy fresh food, a few have asked if they can help for a few hours to earn a little money, and one or two Roanoke residents have come out to help more regularly. “More than the farm employing people,†he says, “we aim to provide a context, a civic social framework, for neighbors to interact, and to launch enterprises focused on what they have to offer.† The farm also teaches people about compost, compost tea, cover crops, use of the broadfork to prepare the soil, and other sustainable farming techniques.

Farm manager Karen Stretton (top photo), employee Rachel Theo-Maurelli and volunteer Donna Grimsley (bottom photo) work in Lick Run Farm’s initial food-producing garden near 10th Street.

Â

Lick Run Farm works in partnership with the Local Environmental Agriculture Project (LEAP) to bring fresh produce into the city’s food deserts. LEAP sells food from Lick Run Farm via a mobile market to low income communities like Villages at Lincoln housing project, where they sell fresh food through the Headstart Center.  LEAP also obtains fruit, vegetables, and other farm products through the Good Food Good People brokerage in Floyd, Patchwork Farm, and other nearby farms. In addition to the mobile market, they also bring products to farmers markets in the West End and Grandin Village neighborhoods within Roanoke.

“Our partnership with LEAP is great, as it allows us to deliver our food where it is most needed,†Rick notes. LEAP has received a grant from the Food Insecurity National Initiative (FINI), a newly funded USDA program, to offer double value SNAP (food assistance coupons) benefits to low income customers, which further improves access.

Support from VABF, Â NRCS, and Virginia Tech

Rick has received support from multiple sources in developing the project. “I love the Virginia Biological Farming Conference, which has been an eye-opening experience for me. We have good soil but not great soil, so we need to build it up. I aim to do this with low-capital methods, relying on hand tools and human labor prudently applied in a way that gets the job done without working ourselves to death.â€

Lick Run Farm has received tremendous support in this endeavor from the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service office in Bonsack (near Roanoke), whose staff, especially Joanne Youston and Bill Keith, “have been awesome resources,†providing both technical and financial assistance through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). “We have contracts through EQIP for building a composting facility, a high tunnel, roofwater runoff collection, and multispecies cover cropping, such as rye, Austrian winter pea, and radish.â€

NRCS staff are “wildly enthusiastic about this honest-to-goodness urban farm,†Rick notes. “Joanne and Bill have been tremendously helpful in developing our application for EQIP, and have visited the farm regularly to document our progress and provide technical support.â€

Through the NRCS folks, Rick met Dr. Cully Hession, professor in Biological Systems Engineering at Virginia Tech, who has arranged for a group of four students to work at Lick Run for their senior class project. They will be working with Rick to develop low-energy, low-capital methods for making and applying compost at the farm, and for managing the water runoff. “We have a group of four very smart, enthusiastic students on the project, with whom we will meet every two or three weeks through the project. We aim to have a completed and working composting facility by the time they graduate.â€Â Another group of Dr. Hession’s seniors is working on water conservation in the Lick Run Watershed, and Rick is staying in touch with them, as their topic relates directly to the farm’s ecological goals.

Time permitting, Rick also plans to have his Virginia Tech students address water management, conserving and utilizing the runoff not only from the composting facility, but also from the hillside and from the roofs of existing and future structures, including the high tunnel and a pole barn. Rick hopes to build a longer term relationship with the Biological Systems Engineering department, having teams of students in future years work on other farm projects, such as how to make and use biochar on site to emulate the Native American method of developing highly fertile terra preta soils in the Amazon Basin.

Tools that work lightly on the soil

One of Rick’s long term goals is to develop equipment that is propelled on the paths and gently works the beds – something like the BCS two-wheel tractor system but with a wider wheel base so that tires run in the path and a tool bar straddles the bed. Rather than inverting the soil to terminate a cover crop, he plans to use a disk harrow, tine cultivator, or other tools that chop the cover crop and work it lightly into the surface.

In Rick’s ideal farming world, tools would be designed to extend and enhance what humans can do with their own muscle. He has been using a scythe to cut cover crops, and finds that learning how to peen the scythe effectively is the steepest part of the learning curve. Peening is the skill of hammering out the blade so that it is thinner and more easily sharpened with a whetstone. Developing other human powered and low-energy-use tools for sustainable, minimum till, small scale farming is one project that Rick hopes that Virginia Tech students in Biological Systems Engineering will take on in future years.

On the cutting edge of sustainable agriculture

In response to my question whether Lick Run is USDA certified organic, Rick says, “we are not certified organic, but our practices go beyond organic.â€Â The farm uses no pesticides, not even those approved under the National Organic Program, because pesticides simply select for stronger pests. “Pests are not the problem,†Rick asserts. “When plants are not healthy, pests act as agents of natural selection. When we are trying to grow food, pests are a threat, but in evolutionary biology, pests are part of the solution. We need to learn from pests regarding soil management and crop nutrition.â€Â In addition to beneficial habitat plantings, the farm does use row covers, trap crops, and other mechanical pest controls when needed.

Rick Williams in the hilltop field, first cultivated in 2014, showing healthy stands of cauliflower, broccoli, and peppers, with flowers in the background providing beneficial habitat

Rick is also very interested in plant breeding, selecting for cold or heat tolerance, specific soil conditions, and pest resistance. He subscribes to a web site for plant breeding in permaculture and perennial crops.

Rick has attended a one day soil foodweb workshop with Vail Dixon of Simple Soil Solutions, Inc. “Now we do compost tea and other methods to build physical, chemical, and biological soil health,†he notes, adding that he plans to add animals in the near future. In his view, animals are “absolutely necessary†for a healthy farming system, a principle of biodynamic agriculture.

Considering the scope of the farm’s mission, and the fact that Rick purchased the land in an overgrown condition just five years ago, I find the current stage of progress impressive to say the least, and one of the most hopeful developments in urban community food systems in Virginia.