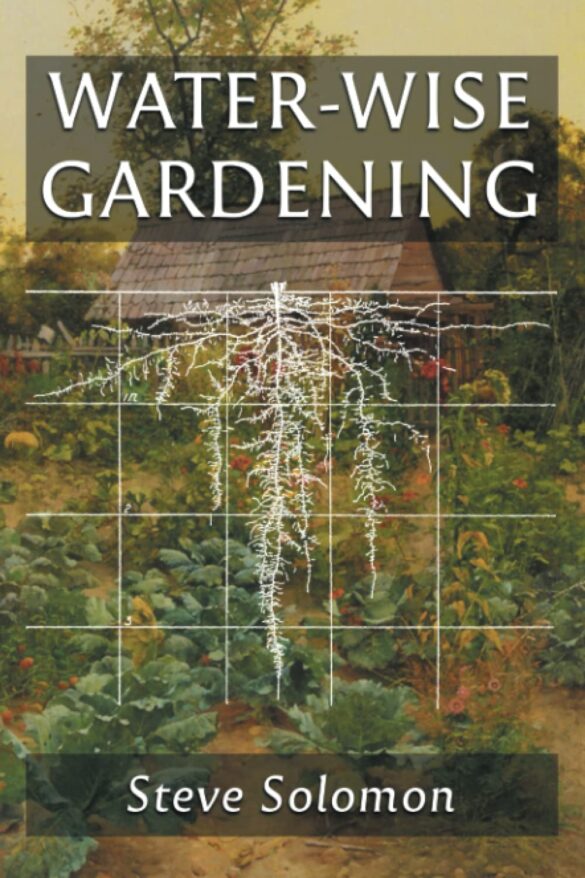

This 2022 book started life as an 81-page paperback Gardening Without Irrigation: Or Without Much, Anyway, and evolved via the 1993 Water-Wise Vegetables: For the Maritime Northwest Gardener (Cascadia Gardening). When he was asked by Good Books if they could republish his work, Steve Solomon decided to expand and rewrite the book for most of North America, and to include wise use of irrigation. For those who don’t know, Cascadia (in Western Oregon) has almost no rainfall from June through September.

Solomon criticizes John Jeavons and the popular French Intensive close-planting bed system for depending on adequate or plentiful rainfall or irrigation without acknowledging that dependency. Gardening with only rainfall requires wider spacing and special planting techniques and schedules to take advantage of seasonal rain and store it in the soil as long as possible. Start weeding early in spring so that weeds do not compete for the stored water. Most moisture loss is transpiration from plant leaves, increased by evaporation from the soil.

There are also tips for those dealing with a sudden reduction in water supply (eg your well dries up): remove every other plant in the row, remove any undersown crops or cover crops, then shallowly hoe to make a dust mulch and fertigate if you can, as dryland gardeners are advised to do. Fertigation is a kind of “rich irrigation†of 2-10 gals/large plant per time, for a total of 50 gals/ plant.

A shallow dust mulch conserves water in the soil by preventing wicking of moisture from unworked soil below. Hoe every few days to maintain the dust. It needs to be restored after every rain, so clearly this method only works for dry climates, or dry seasons. I do wonder what this does ecologically – will the dust wash or blow away?

Spreading organic mulch after the soil has warmed up (not before as that slows plant growth) is another strategy. This book does not advocate weed-blocking thicknesses of 3″ or more, but a light coating to keep the moisture from evaporating. Hoeing under the mulch is possible.

Roots need oxygen, which is in decreasing supply the deeper they go, another natural limit to root depths in addition to moisture limitations. The book includes root drawings in Gardening When It Counts: Growing Food in Hard Times, copied by Muriel Chen from Root Development of Vegetable Crops, a 1927 book by John Weaver and William Bruner.

Compacted soil has less air and is worth improving. If you have clay or compacted iron-rich sand below your topsoil, and you are energetic with lots of time, you can remove the topsoil and bust into the hard layer, mix in compost, then replace the topsoil on top. This is double-digging, and is not as fashionable as it once was.

Alternatively for clay soils, you can add lots of hi-calcium lime (not lime with magnesium in it) into the top 6″ (without raising the pH over 6.5) and then add smaller doses annually. Over time, the lime dissolves and washes into the lower soil, helping the clay flocculate.

Add 1″ of compost to new gardens and work it into the top 6″. Solomon is a fan of tilling. Add ½-1″ compost to the surface annually. Increasing the soil Organic Matter will improve the tilth and improve the water-holding capacity. Increasing the OM by 1% in the top 6″ can store an additional 40 gallons of water per 100 sq ft. Increases of 3-4% can provide as much as 200 extra gallons. This is not a linear equation. Adding more and more doesn’t increase the water capacity more and more. Your soil will stabilize at some OM level and adding more simply causes the soil to release nitrogen, especially in hot climates. Reaching 4% OM in steamy Arkansas can be as difficult as reaching 10% around Portland, Oregon. Green manures can help raise the OM for a few years, but then the extra N loss cancels the extra added.

Reduce runoff and help rain soak in by planting along contours rather than up and down the slope. Permanent mulch is not a good answer, if your frosts don’t go deeper, as populations of slugs, earwigs and pillbugs will increase.

Another aspect of dryland farming to bear in mind is: if your climate provides rain in spring and none in summer, your spring crops might use up all the water, making growing summer crops without irrigation impossible. One way to work with this problem is to grow more spring crops.

A way to avoid midsummer stunting caused by large plants running out of nutrients is to dig large 12″ deep planting holes, 12 sq ft apart, filling them with prepared fertile soil and making slight hills 16″ in diameter. Press five seeds into the soil at the center. This works for tomatoes, squash and big brassicas. Broccoli heads can grow the size of dinner plates with this method, provided you didn’t sow a “compact†variety. Hybrids do better than OP varieties, which have run downhill in recent years. This doesn’t sound practical for commercial growers, but can work well for backyard growers who like large plants.

Direct sowing has some advantages over transplanting, especially in terms of minimizing root damage, reducing the need to water. Another dryland grower told me that roots of direct-sown crops grow aligned with the foliage above ground. This matters most with vining crops and leads to the soil above the roots (i.e. below the leaves) losing less moisture.

You could till the soil for your summer crops a month ahead of sowing, roll and then cover with a light mulch. To re-establish the capillarity of the soil you can roll a wheelbarrow over the positions for widely spaced rows and ignore the spaces in between.

It can help to soak seeds or even pre-sprout them just until roots start to emerge. Fluid sowing is another option. Pre-sprout the seeds for a few days and make a gel of 2-3 tablespoons of cornstarch in a pint of boiled water. After cooling it, try stirring in some seeds. If the mix is too watery to support them, heat up the gel and add more cornstarch. If too thick, add more water. Put the mix in a plastic bag and at your prepared furrow, snip a corner off the bag and squeeze out the gel.

For establishing winter crops, you can use an outdoor nursery seed bed to grow transplants to set out after the summer crops are finished.

The author provides his recipe for his Complete Organic Fertilizer (COF) to be used with ¼ -½” layer of compost each year. Provide a full dose of COF before planting anything, then side dress further from the stems with more COF every few weeks, up to a total of 6 additional quarts per 100 sq ft over the season. Foliar fertilizer sprays can also help, although the author disparages the Organic ones.

The author provides his recipe for his Complete Organic Fertilizer (COF) to be used with ¼ -½” layer of compost each year. Provide a full dose of COF before planting anything, then side dress further from the stems with more COF every few weeks, up to a total of 6 additional quarts per 100 sq ft over the season. Foliar fertilizer sprays can also help, although the author disparages the Organic ones.

Reduced plant density is one of the keys to dryland gardening or farming. When plant canopies close above the ground, their roots underground are also meshing and competing for water. Lowering the plant density does not reduce the yield for the space as much as we might assume. A plant density of one-eighth that recommended for intensive planting might result in a yield of one-half of a dense planting. Plants at reduced spacing grow faster and bigger.

I found the recommended spacings quite startling! I grow vegetables in central Virginia, with a statistically even 3.5″ rain per month, and before that I gardened in Northern England, with a statistically similar rainfall. Solomon recommends transitioning to dry gardening by giving each plant 25% more area than you previously did, increasing that space by 25% each year until the plants stop getting bigger. If you are growing lots of a particular crop, you could speed things up by growing several rows, using different spacings.

Around this point in the book, I started to wonder why someone would choose dry gardening. It takes a lot of land, which has its price, and requires wide swathes of bare or lightly mulched soil. Why not invest in getting a well drilled? I know there are some places where underground water is not to be had, but I think that’s less common. Am I wrong?

The next part of the book is an A-Z of crops to grow. In a spirit of honesty and humility, the author admits to not knowing everything about every crop in every climate and asks for our patience.

Crops suitable for dry gardening include all the larger brassicas, but not the less vigorous smaller broccoli, quick-maturing cabbage and kohlrabi, early Brussels sprouts, or Chinese cabbage. Larger plants that have longer to grow are more likely to find enough soil moisture. Overwintered Purple Sprouting Broccoli is worth trying if your winters do not go much below 10F, perhaps zones 8a and milder. If winters are mild enough, try what in England are called spring cabbage or spring greens. Spring Hero is a good variety. Sow in late August or early September, transplant in fall, harvest in spring before or after heading.

Spring lettuce must be given a space of at least 12″ x 36″, up to a 36″ diameter circle. If you have no irrigation and are reliant on winter rain, you get one single chance to sow carrots in mid-spring. Perhaps counter-intuitively, the large autumn varieties are the ones to choose. They grow steadily as soil water allows, without getting fibrous. Make rows 4′ apart and thin to 6″ in-row. Wide spacing can lead to very large carrots, broccoli heads and potatoes, but the plants occupy the land for a long time. Is bigger always better?

Cucurbits don’t transplant easily due to root damage, and direct seeding doesn’t work if the soil is too cold or wet. Solomon has a strategy: Sow some squash first, as it is the cucurbit most tolerant of chilly, damp conditions. If the seeds don’t germinate in a week, sow some more. Continue until some germinate, then sow some cucumbers. Sow cucumbers once a week until you get some germination, then try some melons. To increase success with cucurbits, pre-sprout (chit) the seeds in a roll of damp paper or fabric towels. Don’t soak the seed first. Put the damp roll or sandwich in a plastic container in a warm place (75F/24C). Orient the seeds so the roots can obey gravity without looping, and start checking after 36 hours, and then every 8 hours. Plant the seeds in dampened soil in the garden before the roots are longer than the seed. Don’t water until the seedling emerges.

Potatoes grown in good fertile soil can contain 11% protein and taste delicious without ketchup or other additions. Supermarket potatoes contain around 8% protein. USDA nutritional studies over the past 50 years show that the average nutritional value of vegetables has declined 50%. In the early days of Idaho potato-growing, before irrigation added to the annual 10-15″ annual rainfall, growers set the seed pieces 18″ apart in rows 5′ apart. You can grow giant potatoes this way, and if you are short of seed potatoes and/or water, and need to feed a crowd, or fewer people for the full year, this may be the way to go.

Sweet potatoes are covered although the author has not personally grown them. Southern growers consider irrigation essential. Rutabagas are a challenge to grow without irrigation and do best sown in late June or early July, which is too late for those hoarding spring rain in the soil.

Squash roots can grow huge, including a deep taproot. Solomon advises giving each plant the amount of room the same as its maximum vine length, meaning a 10′ diameter circle for the bigger winter squash, and almost that for crookneck summer squash. If summer has no rain, yields of squash will be low unless you fertigate every 2-3 weeks. This will increase the yield by 45lbs.

Indeterminate tomatoes are suitable for dry gardening, because they have large root systems. Solomon adds stakes about 2′ apart in widening circles around each plant, to tie in the vines. They need about a 7′ diameter circle each.

The author is growing food for two people (oldies who don’t eat as much as they once did, as he points out). My impression is that this kind of gardening works for experienced gardeners growing on this kind of small scale. It doesn’t sound like it would work commercially.

The next chapter of the book gives the author’s own 60′ x 125′ ft garden plan from the 1990s, and some old photos. He has one 4′ wide 125′ long raised bed with 125′ single rows on either side. There are two lines of low-angle sprinklers along the edges of the raised bed. The reach of those is about 18′ and they each use 1gal/minute. They are 12′ apart. The raised bed is planted with crops that benefit most from irrigation.

The following section “How to make frugal and effective use of irrigation†includes a brief explanation of how soil is formed, what water does in the soil, and the hazards of over-watering (nutrients get washed down into the subsoil, along with oxygen), followed by tips on handwatering with a hose from John Jeavons, the intensive gardening expert, who advocates watering back and forth until the wet soil stays shiny for a certain length of time. I learned this as a 10-second rule, but, unsurprisingly, the time depends on your soil. Soloman suggests trying different ‘shine durations’ and then digging holes to see how deeply the soil is saturated. Once you know how long the shine lasts once you have got a suitable depth of watering, memorize your answer! Germinating seeds, young seedlings, new transplants and radishes need water most days.

Sprinklers can do the watering for you, freeing you from standing there with a hose. The author has a chart of how much moisture remains in the soil once plants have reached a permanent wilt stage (only 20-33%), a temporary wilt stage (50%), and the minimum for successful intensive vegetable beds (70%). There is another chart of the water needed to bring 12″ of soil from 70% to 100% capacity, and one of the average summertime daily soil moisture loss on non-rainy days (¼-½”). This helps you plan how often to water. How do you know when moisture has fallen below 70%? Take a handful of soil and form a ball. If it is wet, it’s over 70%. If it sticks together but breaks apart under thumb pressure, it’s around 70%. If you can’t form a ball, it’s below 65%. If the soil is sandy, you won’t ever be able to form a ball.

Sprinklers may not distribute water evenly, so test those you already have, and buy good agricultural-quality ones in future. Determine your water pressure and flow rate (time filling a 5-gal bucket). Suitable impact sprinkler nozzles should emit 1.25-2.5gals/min. Rainbird 14VH is a recommended type for vegetable growers. It comes with a range of nozzle sizes. The book has charts of nozzle sizes with the corresponding throw radius at various water pressure rates, along with gals/min distributed. Another chart shows application rates from various sized nozzles and two representative pressure rates. Small bore nozzles and application rates up to ½” per hour generally work well for vegetable gardens.

To achieve an even application rate over the whole of the area irrigated, a rotating impact sprinkler must deposit around nine times as much water around its periphery as at its center. Most growers devise a system of overlapping circles to even things out. To water a smaller radius, various diffuser flaps and adjustable screws can be used to interrupt the flow, but these make distribution less even. Models without these devices are made that put only twice as much water at the center as at the periphery. Avoid the bells and whistles you don’t need.

High-angle sprinklers throw a greater distance than low-angle ones. Choose high-angle sprinklers with 1/16″ nozzles to run all night on clay soils, minimizing evaporation, and getting good value for the water applied. Nelson makes turbine-powered designs that provide even coverage for a fair price. The book has good drawings of different sprinklers.

You can get more and better drip irrigation information elsewhere. Solomon seems to believe that a 100′ length of drip tape has to be trashed if it gets one cut. This definitely isn’t the case. It sounds like he just never learned to like drip tape.

The last chapter consists of charts of suggested plant spacings based on the author’s direct experience and informed guesses. The reading list includes 16 classical Western texts from 1920 to 1992.

This book is one of about 15 by Steve Solomon, some reissued with new titles. His most well-known work, Growing Vegetables West of the Cascades, has been published in seven editions, 1983 to 2015. I liked Gardening When It Counts: Growing Food in Hard Times (2006) but was not alone in disliking the superior tone in The Intelligent Gardener: Growing Nutrient-Dense Food (2012). I’m glad he has mellowed.

Book Review by Pam Dawling, Author of Sustainable Market Farming: Intensive Vegetable Production on a Few Acres, and The Year-Round Hoophouse: Polytunnels for All Seasons and All Climates