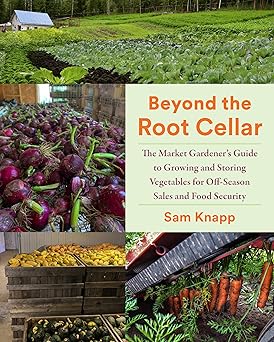

Book Review by Pam Dawling, Author of Sustainable Market Farming: Intensive Vegetable Production on a Few Acres, and The Year-Round Hoophouse: Polytunnels for All Seasons and All Climates

Beyond the Root Cellar: The Market Gardener’s Guide to Growing and Storing Vegetables for Off-Season Sales and Food Security

Sam Knapp, 2024, 272 pages, 8 x 10 inches. $45.

Chelsea Green Publishing

I have been looking forward to this book, because I appreciated several articles by Sam Knapp in

Growing for Market magazine. This book addresses a gap in most local food systems. It is the

first (only) book of this kind, and it’s very good. Sam Knapp is a pioneer.

Sam worked as an engineer before becoming a farmer in the Michigan Upper Peninsula, and then

in Fairbanks, Alaska, where he runs a winter-only CSA from Offbeet Farm and sells to local

groceries. Thanks to his scientific background, he understands and explains energy efficiency, as

well as spreadsheets, very well.

This book will up your game in storing winter vegetables, as it includes the vital information on

choosing, growing, harvesting, trimming, processing, curing (if needed) and storing eighteen

crops, as well as details about constructing storage spaces and operating climate-control systems.

The author has considered lots of sources of information, and when information conflict, he has

presented the experience of farmers, and the results of scientific trials and studies. There’s plenty

of useful info for small scale growers not on the point of building big storage buildings. Anyone

growing any storage vegetables will get valuable information.

North American countries could use a lot more locally grown winter crops. There is not much

competition yet. A storage farmer wanting to also provide training for apprentices, or other ways

of training, would be offering a rare commodity.

Storage crops offer a lifestyle of intense large-scale work in the fall, followed by a “selling

season” with reduced or no outdoor work. Storage crops take a little time to plant and tend

during summer, leaving lots of the week open for other activities. The work flow is less likely to

cause burnout than farming for summer and fall sales.

The first part of the book (about 60 pages) is From Field to Storage. Here we learn about

choosing appropriate crops and varieties, recognizing maturity, harvesting, post-harvest handling

and putting the produce into storage. The author’s father Phil spent many weeks of his retirement

taking the photos for the book, as well as helping with construction work. The uncorrected proof

I am reviewing has the photos rendered in greyscale, such is the lot of reviewers!

Some vegetable crops increase their cold-hardiness as daylight and temperature decrease by

producing sugars and alcohols in their cells, lowering the freezing point of the sap. Others

transition to a state of reduced metabolic rate, activated by plant hormones or low temperatures.

There are two kinds of dormancy: hormonally controlled dormancy and environmentally

controlled dormancy. The latter crops will sprout if exposed to warm temperatures and moisture.

Crops with hormonally controlled dormancy will not resprout until triggered by a change of

hormones, often due to cumulative exposure. Aha! New information for me. Which crops are

which? Sweet potato dormancy is environmentally controlled. Any extended exposure to

moisture and temperatures above 60F (15.5C) leads to sprouting. Potatoes, on the other hand, can

stay dormant for months even if exposed to good growing conditions. Onion sets are an example

of dormancy maintained by environmental conditions – temperatures above 85F (29C), and dry.

Onion sets when planted in cool spring conditions, grow into larger onions.

Choose crops that reliably mature in your area. The number of frost-free days, soil temperatures

and daylength can all affect maturing. Did you know that Butternut squash requires darkness to

set fruit? Avoid crops or varieties that easily bolt, split, break, or bruise, or are susceptible to rots.

Read the small print in the seed catalogs. Collect your own data, perhaps on your phone. The

book has some tips and a Variety Trial Datasheet. Record storable yield per area, as well as culls

as a percentage of total yield.

The next chapter is about harvest. As this is going to be a major part of the farm work, Sam

advocates careful harvest planning. There are charts in the book to help you track progress.

Consider your last date for harvesting each crop, and the amount of time the harvest could take.

Make sure not to plant more than you can harvest in the window! Make use of any past harvest

records you have. Ask nearby vegetable growers too. Can you harvest 10 100ft x 5ft beds of

cabbage in just over one day? How many days do you need to allocate to carrots? Can 2 people

hand-harvest 900lbs of carrots in 8 hours?

Past climate data are helpful. The National Weather Service has a Past Weather page. (I like

Weatherspark myself.) Look for daily normal, average high, low and mean temperatures for each

day at that time of year. Plan to harvest before the date when the mean temperature reaches the

threshold for chilling injury of that crop. It may well be earlier than you had expected.

Remember to factor in some days for bad weather! Add rowcover or mulch in the fields if you

need to buy time. Watch the crops and triage if necessary. This means three categories: crops it’s

imperative to harvest, ones you must let go of, and ones to harvest if at all possible.

Garlic and onions will most likely be first, and are very prone to troubles if left too long in the

field. Cold-sensitive crops are next: winter squash, pumpkins and sweet potatoes. These all

accumulate chilling injury below 50F (10C), leading to deterioration in storage. Next are the

crops that are damaged by hard frosts: cabbage, kohlrabi, rutabagas, turnips, winter radishes,

beets, celeriac, potatoes. Beets lead this group. The final group includes crops least damaged by

hard frosts: carrots, parsnips, sunchokes, leeks.

Try not to be Nervous Nellie, harvesting sooner than necessary: many crops develop better

flavors in colder weather. Also consider the extra electricity you’d use for cooling for longer.

Common advice sets 28F (-2C) as the limit for intermediate crops such as beets, and 24F (-4C)

for the most cold-hardy crops. The duration of cold temperatures as well as the daily mean, (and

therefore the high temperature that day) are important parts of the equation.

There is some discussion of harvesting equipment, from knives to the intriguing Scott Viner

harvester, which runs a digging shoe below a row of roots such as carrots, at the same time as a

set of rubber belts grabs the carrot tops just above the crowns, and lifts them up, dangling by

their tops. Next there is a knife that cuts the tops and deposits the carrots onto a chain conveyor,

shaking soil off as it goes. The carrots are dropped into a following truck or wagon. A fast hand-

worker can harvest 200-250lbs carrots per hour on a clean bed that has been undercut. A Scott

Viner with 3 or 4 workers to tend it, can harvest 2,500 to 3,000 lbs per hour. Dryish soil is

needed.

Harvest-handling equipment consists of containers and compatible equipment to move the filled

containers. Carts and wheelbarrows can move about 200 pounds of well-balanced crops.

Containers are generally either small enough to lift by hand or large enough to need a forklift.

When considering upgrades, decide your handling equipment first, and get containers that fit

with those.

After harvesting, the crops generally need attention before storing: trimming, washing, curing,

grading. There are several reasons for trimming root crops. Most leaves will rot in storage

anyway, so they have no future. Trimming saves storage space, makes washing easier, and

reduces moisture loss. Ideally, leave only short stubs of the leaf stems, which will dry out quickly

and are unlikely to rot. If the trimming can be done in the field, all the inedible organic matter of

that crop returns to the soil, plus you have less to haul away.

Potatoes and sweet potatoes must be cured, a process when cut surfaces heal over and become

coated by a protective waxy layer. Cured skins become more firmly attached to the tubers,

preventing further damage.

There is discussion on whether to wash root crops before storage. It depends on the equipment

you have. With electricity, washing pre-storage is a viable option. Without it, conserve moisture

in the veggies by leaving the soil on them. If you have cooled storage, you may prefer to wash

veggies while the weather is warm, and the soil is easier to remove. Barrel washers are

discussed, including farm-made ones, both hand-cranked and electrically powered, and

purchased small-scale models.

Chapter 4 Into Storage contains lots of useful tips. In the first few weeks after you store the

crops, they need attention to ensure conditions are right, and removal of vegetables that are

starting to rot. You can’t sort through large amounts, but cast an eye over the top layer. Sam

divides crops into four groups according to optimal storage conditions. He acknowledges that

you might have to compromise if you can’t provide the ideal for everything.

The cold and damp group (32F, over 98% humidity) works well for most winter storage crops,

especially roots and leafy crops. Alliums do best at 32F and 60-70% humidity, fairly cold and

fairly dry. Compromise on the temperature, not the humidity! Avoid 40-50F for garlic, and 50-

86F for onions. Potatoes do best at 38-45F and above 95% humidity, as temperatures below 38F

can cause chilling injury, leading to browning of the flash when cooked, especially fried. Higher

temperatures lead to faster sprouting. Sweet potatoes are best at 57-60F and 85-90% humidity,

and colder temperatures lead to chilling injury; higher ones to sprouting. Winter squash and

pumpkins do best at 50-55F and 50-70% RH: higher temperatures lead to shriveling and

yellowing of green varieties; chilling injury shows as pitted skin.

Choose storage containers that allow airflow, can stack, are not too heavy. Large farms use

palletized containers. There are plastic macrobins, farm-made wood bins and cardboard Gaylord

boxes with wood pallet bases. There are woven super sacks that fit on a pallet and can be lifted

with pallet forks using the large loops at the top. These are cheap but don’t stack unless put

inside a container such as an Intermediate Bulk Container (IBC) frame.

Alternatives are smaller containers such as 5-gallon buckets, plastic 18- and 27-gallon totes with

holes drilled in them, as well as 50lb grain bags. This chapter has a chart of bulk density of

storage crops, to help with planning. A 27-gallon tote can hold 95-110lbs of beets. Traditional

storage methods such as damp sand or sawdust are fine for a few hundred pounds of veggies, but

impractical for large quantities. Also, sawdust, burlap, wood shavings and peat moss can impart

their flavor to the vegetables.

Part 2 of the book (about 60 pages) covers designing structures and practices, including the

business side. Starting a storage farm does involve high up-front costs for buildings and

equipment, although it’s fine to start with the buildings you have. Efficiency, efficacy and scale

are important, because storage crops don’t generally sell for top prices, although on the plus side,

you will be selling into a relatively open market. Be sure to match the scale and costs of your

infrastructure and production with your likely sales. Small intensive farms (1-7 acres of storage

crops) with close crop spacing can produce high yields, such as 25,000lbs/acre. Average yields

are 10,000lbs/acre for larger mechanized farms.

This book provides up-to-the-minute details on modern construction and insulation materials. It’s

not a construction manual, more a technical decoding guide and a shopping advisor, providing

the overview you need to have useful conversations with contractors. Or perhaps to provide the

knowledge to embolden you to construct your own storage spaces.

There is help with estimating seasonal income and losses (there is are charts of shrinkage

estimates over various durations). There are suggestions on how to sell crops before the storage

losses become too high: figure out a percentage loss to accept, and if you still have produce at

that point, put it on sale! And adjust your plan to grow less of that crop next year. There’s an

excellent working example of squash loss. Note harvest weights, sales records, total losses, the

selling quality and the effectiveness of your sales strategies. Don’t neglect other goals and ethics.

Is your goal to maximize your income or to provide food for your community for as long as

possible?

Traditional root cellars are useful. If you are starting from scratch, compare with shipping

containers (either insulated or uninsulated and buried), walk-in coolers (used?), CoolBots,

purpose built above-ground insulated buildings, or cellars below other buildings. Your climate

will play a big role in choice of storage. Farmers with milder winters are able to manage with

less-insulated structures, as their heating and cooling use will be lower.

This section includes explanations of R-value (insulation), dewpoint, temperature, relative

humidity (RH), vapor barriers, various insulation materials, and which ones Sam recommends

for various situations. There are instructions to slope floors, deal with joins in sheet materials,

avoid thermal bridging, condensation and moisture transfer. Lots of help for those building their

own structures or instructing a contractor.

Climate control is covered very thoroughly and clearly. Having a good storage structure gets you

part way to your goal of keeping crops dormant while retaining moisture and limiting chilling

injury. Refrigeration and/or heating might be required. There’s help with calculations and costs

and choosing suitable equipment.

There’s a 3-page section comparing CoolBot (which uses AC technology) and commercial

refrigeration. CoolBot has a limited range of operating temperatures. This might be sufficient if

your climate is relatively mild, and you can use cold outdoor air most of the storage season.

CoolBots don’t work so well with outdoor temperatures below 25F. Oversizing the CoolBot for

the space or using multiple CoolBots in the same space will help with initial cooling of large

harvests. Commercial refrigeration units can cool spaces faster than CoolBots. Single-AC

CoolBot systems use less energy than refrigeration, but it’s unclear if multiple-AC systems do.

CoolBot has a good website and customer service.

There are recommendations on dehumidifiers and humidifiers, not forgetting the “put water on

the concreter floor” method. Good airflow is vital for achieving even conditions throughout your

storage space: consider fans and pulling in cold outside air.

Part 3 (about 46 pages) is the storage crop compendium, where the needs of 18 storage

vegetables are clearly described in precise detail, including responses to ethylene, and also

common problems. This is the section I’m going to use immediately. If this is the only part of the

book you need right now, buying the book is worth it! Sam has done a lot of sleuthing to compile

very specific information. His longest storage recommendation seems to be 4-6 months, although

longer is definitely possible in our climate.

The final section of the book (about 65 pages) offers profiles of nine storage farms from North

Carolina, Wisconsin, Washington, Michigan, Minnesota, Vermont, Manitoba and Alaska. Each

profile ends with a paragraph of advice for new storage growers. These profiles make a good

read, suggesting several workable systems, from ¼ acre improvised start-ups, through converted

barn root cellars and dairy barns supplemented with refrigerated trailers or shipping containers,

to purpose-built spaces on new farms requiring tree clearance or a set of walk-in coolers and

trailers. Land in storage crops is up to 7 acres (25 acres in one profile) of storage crops, mostly

grown on a bed system. Some use off-site rented storage. Most of the farms run CSAs and do a

lot of harvesting by hand. Some focus on 8 or fewer crops, others diversify as much as possible.

Some combine being a storage farm with growing summer crops, some specialize and some

combine with farm-related businesses such as a fermentation business.