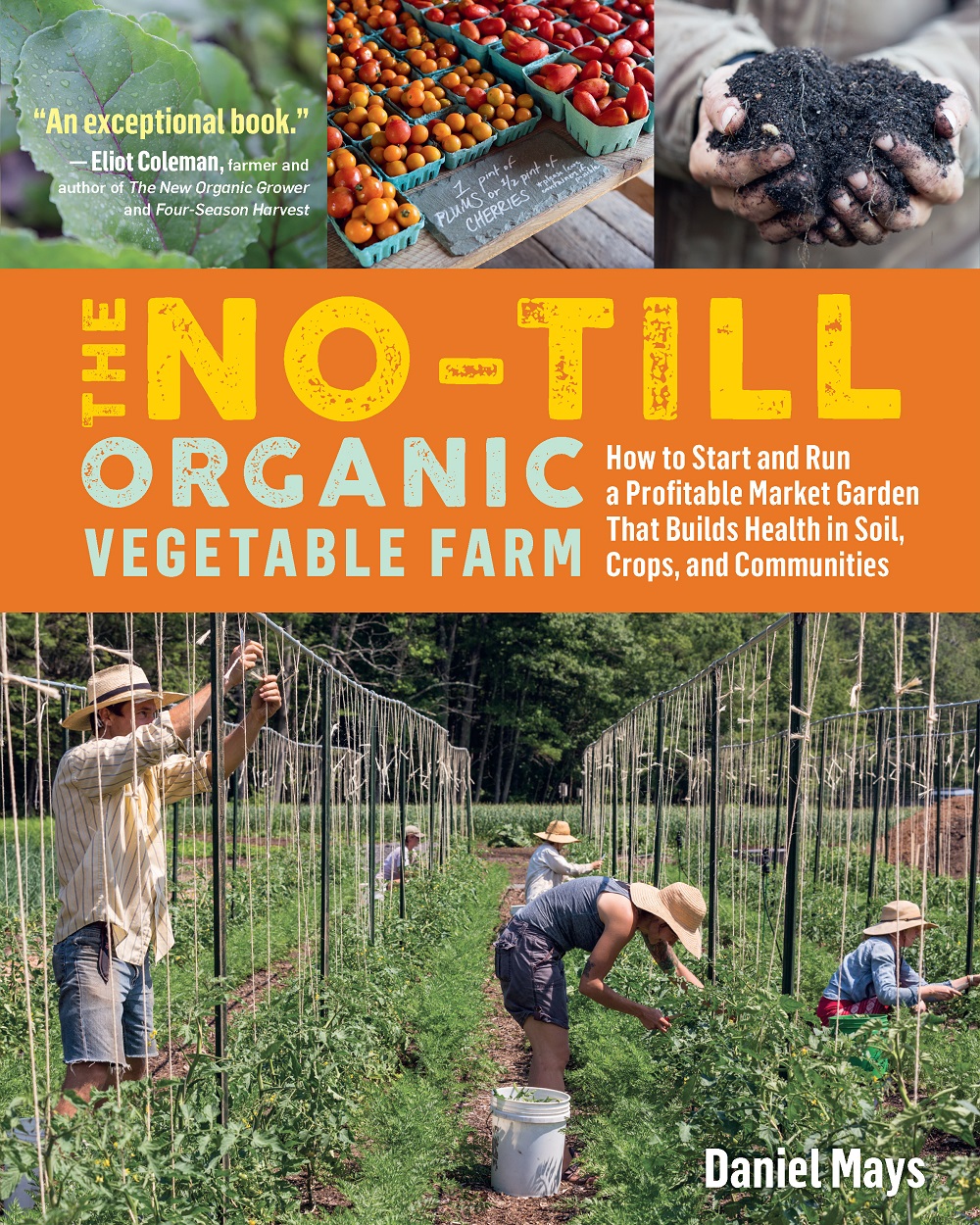

Book Review: The No-Till Organic Vegetable Farm: How to Start and Run a Profitable Market Garden That Builds Health in Soil, Crops, and Communities, Â Daniel Mays, Storey Publishers, 2020. 230 pages, color photos throughout, $24.95.

Book Review by Pam Dawling

The No-Till Organic Vegetable Farm is a great help to those moving towards more No-Till. This book is full of practical details, and efficient and effective no-till practices, such as how to manage large tarps. This is also a beautiful book. The photos are crisp and inspiring, the drawings clear and informative, the charts well organized and easy to use. The aerial photo shows a poster-farm! Frith Farm is a small-acreage vegetable farm using raised beds, in the style of Jean-Martin Fortier, Ben Hartman, Curtis Stone and others. “No-till human-scale farming is about so much more than avoiding tillage.†Here we can learn about healthy soil, high productivity, fewer weeds, lower costs and a more natural way of growing food.

We have had several new books on no-till in the past year or so. I have reviewed Bryan O’Hara’s No-Till Intensive Vegetable Culture, and Andrew Mefferd’s Organic No-Till Farming Revolution: High-Production Methods for Small-Scale Farmers. Any reduction in tillage is a good step: you don’t have to commit to permanent no-till everywhere. I’m glad we’ve moved on from the early no-till days when it was considered that all tilling was always bad, but practical advice was lacking.

The book includes some hard-to-find topics, such as acquiring capital, designing and setting out drainage and irrigation systems for both drip and sprinklers, and integrating livestock in a vegetable farm. Minor grumble: the index seems a little light. Fortunately, the book, like Frith Farm, is well-organized, and topics are easy to find.

Daniel started Frith Farm in Scarborough, Maine, in 2010, in his mid-twenties, borrowing $180,000 at 3.8% interest and buying a property with five open acres and a crumbling house and barn.  He had “eighteen years of expensive education and an embarrassing lack of hard skills.†His first year, he provided for a 40-member CSA from less than one acre. The farm now supplies a 150-member CSA, four natural food stores, a farmers’ market and a farm stand. They sell about $300,000 worth of food, using 2.5 acres in cultivation and 2.5 acres of pasture. Almost all of the work is done by hand, by a crew working  a 45-hour-week for 8 months, then having four months off.

Daniel recommends consistent bed dimensions, even if compromising the land geometry. He has 16 plots of 12 beds, each 100ft long, on 5ft centers. This bed-width increaseses the amount of growing space compared to 30ins beds. He’s over 6ft tall, so jumping over a bed is no problem. I don’t know about the rest of the crew. There are drivable surfaces between the plots and wood chip paths between beds. Without tilling, you minimize erosion, and the conventional wisdom of keeping rows across the slope, not up and down it, isn’t so vital.

Daniel recommends soil testing and an initial supply of inputs to jump start your soil health and enable you to earn a living. You’ll probably be buying compost your first year: 54 cubic yards ($25-$50/cubic yard) will provide 3ins cover on 6,000 sq ft (one Frith Farm plot). Once biological soil health is established, few imported soil amendments will be needed. You will need lots of mulch every year, such as leaves, straw, woodchips. Frith Farm uses 130 cubic yards of leaves per acre each year.

Daniel recommends soil testing and an initial supply of inputs to jump start your soil health and enable you to earn a living. You’ll probably be buying compost your first year: 54 cubic yards ($25-$50/cubic yard) will provide 3ins cover on 6,000 sq ft (one Frith Farm plot). Once biological soil health is established, few imported soil amendments will be needed. You will need lots of mulch every year, such as leaves, straw, woodchips. Frith Farm uses 130 cubic yards of leaves per acre each year.

To go from a grass field to a set of ready-to-plant beds, some no-till growers do one initial tilling and maybe subsoiling to establish beds (rent or borrow the equipment). Daniel says “Don’t let purism keep you from actually breaking ground – it is better to start farming imperfectly than never to start at all!†Frith Farm tills with a Berta rotary plow on their BCS walking tractor, one 10ins strip at a time. We use a Berta plow to remake paths in our raised beds – it is a wonderful tool for that.

A second method of killing grasses and weeds is to mow closely and smother the plants with tarps. This takes 3-52 weeks, depending on the weather and plant species. This works for beds you plan to bring into production next year. Use a 5-6 mil thick black and white silage trap, black side up. Weight and wait! Daniel’s ingenious “tarp kit†consists of a pallet with enough cinder blocks to hold down a 24×100 ft tarp, which is folded and set up on top of the blocks, safely out of the way of tractor forks. The kit is moved to the next site, then returned to the pallet when its work is done. I’ve been interested in trying tarping, but muscling huge sheets of silage tarp and enough weights to hold it down was quite off-putting.

When you and the dead plants are ready, remove the tarp, spread compost thickly and plant. If the soil is compacted, use a broadfork before spreading compost. Tarping is also a valuable method for flipping beds between one crop and the next.

A third method of establishing new beds is to mow, amend the soil, cover the whole area with thick mulch, topped with compost and plant into that. To succeed, use an initial layer that lets no light through. Â This method involves lots of work and mulch.

Seedling production is major at Frith Farm, as transplanting fits well with no-till. They recommend 500 sq ft of greenhouse space per acre of field production. They have some very practical “benches†which are sawhorses topped by custom pallets holding 12 standard 1020 flats. Two people can carry a full pallet, saving lots of time transferring one flat at a time.

Frith Farm uses soil blocks, mixing in a cement mixer. Winstrip trays are much quicker than making blocks, but they prefer the smaller cost and space saving of soil blocks. They use four sizes of standup blockers, but not the ¾†miniblocks, because those dry out too fast. They have tried the paperpot planter and found it unsuccessful when planting into stubble, worth considering before spending $3000.

One key to successful transplanting is appreciating the sublime experience of setting a plant in the ground with your own hands. Another is to have enough hands to get the job done! A third is watering soon after planting. They use a rolling Infinite Dibbler, a homemade oil-drum dibbler and a special 6-plant garlic dibbler For direct seeding, Daniel likes the humble Earthway seeder, even using it for cover crop seeds (the beet plate for the grasses). The Earthway is rugged, affordable, and works well in no-till beds.

Irrigation is another aspect of vegetable production that Daniel has well figured out. Here is a good clear explanation about well depth, flow, recharge rates, costs, water quality and all the facts you never needed to know if you use city water. The book includes a very clear pipe layout superimposed on the bed plan.

Daniel will help you decide between drip irrigation and sprinklers (or some of each). He recommends Senninger Xcel Wobblers. He likes Wobblers with a 1gpm flow each, covering 6 beds with a line of 4 sprinklers. They run 12 sprinklers at once. This kind of detailed step-by-step calculation can be hard to find. Here’s another instance where the book pays for itself with just one piece of information! Daniel uses driptape only for long-season crops that are prone to foliar diseases, otherwise, he likes the simplicity of sprinklers. Follow Daniel’s advice and bury all main and lateral pipelines deep enough not to hit them when digging. A hose reel cart is a helpful thing to have to make hand-watering less of a tangled mess.

Daniel avoids rowcover unless a crop has two reasons simultaneously. Pests and diseases indicate imbalance, underlying issues with soil health, crop rotation, biodiversity. Work to rebalance and make improvements. Work towards being a No-Spray farm as well as No-Till.

The chapter on weeds opens with the saying “We till because we have weeds because we till . . .!†Weeds are an ecological mechanism for keeping the soil covered and full of roots. The “simple†solution of never letting weeds seed is less work in the long run, more work at first. It relies on working only the amount of land you have enough skilled hands to deal with. Two skilled fulltime workers per acre.

When is thick mulch not helpful? In early spring when you want to warm the soil. At Frith Farm, the soil is frozen from November to late March. Beds that finish too late to plant an overwinter cover crop get composted and covered in leaf mulch. They rake this leaf mulch off the beds into the paths in early spring, and spread a layer of compost on the beds, allowing some warm-up time. The dark compost absorbs the heat from the sun.

“Flipping the bed†after a crop may be simple if it was a root crop with few weeds. If the crop leaves a lot of bulky residues, mowing and tarping can restore the soil to a usable state in 5-10 days in warm weather. You may need to dig out perennial weeds, or add soil amendments, and another 7 barrows of compost per 100ft bed (2.5 cu yards/1000 sq ft), but soon you are good to go. They have a smooth compost spreading operation. A tractor driver delivers buckets of compost directly into wheelbarrows lined up at the head of the beds. People push the barrows down the paths, dumping out several shots of compost, raking the compost out to cover the whole bed surface.

Solarization with clear plastic during warm sunny weather is another way to kill weeds. If the edges of the plastic are buried, weed seeds and pathogenic fungal spores are also killed. If you want to kill weeds or crop residues without all the other life forms in the top layers of soil, using black plastic tarps is a safer way to go. The soil temperature does not get as high, but the removal of light does help kill plants. The book has a graph of days of tarping versus temperature. More than 25 days at an ambient temperature of 50F, about 9 at 65F, and only one day above 85F.

They have an ingenious foot-powered crimping tool for killing tall cover crops instead of mowing. Called the “T-post stomperâ€, this is a partner dance with one person at each end of a T-post lying across the bed. The T-post is tied with twine to the “inner†foot of each partner and includes a long twine loop that is hand-held.

No-till cover crop planning takes care. Plants die in three ways: they finish their lifecycle, they winterkill or they are starved of light or water. In no-till farming, the tools are the mower, winter, and tarping, or some combination of these. A sequence of photos shows beds from seeding the cover crop in September to healthy summer brassicas with no weeds in sight. A spring cover crop sequence shows peas and oats sown in April, tarped in June, direct seeded in storage radish in summer. Shorter sections on summer and fall cover crops follow.

Daniel has a chapter on integrating livestock with vegetable farming to increase diversity and net productivity of the farm. The symbiosis between soil, plants, animals can lead to creation of more soil, and increased fertility. Chickens are easy to keep, although if you want poultry that don’t scratch up the soil, get turkeys. (Daniel has a punny photo of turkey on rye.) Sheep are easier to fence than goats, and are smaller than cattle. Be wary of pigs. They can act like obsessed tillers and do lots of damage.

Harvested crops remove nutrients from the farm soil, and these nutrients can be replaced by farming for a very healthy soil biology. Healthy soil draws carbon and nitrogen from the air, and makes previously “inaccessible†stores of nutrients available to the following crops. Use compost, leaves and other organic mulches until you max out the recommended level of some nutrient. If your soil is then unbalanced, you will need to bring in missing nutrients.

The chapter on harvest sets out efficient user-friendly methods at Frith Farm. For a pleasant wash-pack space, you need a roof, a floor with good drainage (could be wood chips), mesh or slatted tables; hoses and sprayers; tanks to hold water; a salad spinner, a barrel root washer; good scales; flip-lid storage totes; walk-in coolers using CoolBot technology; and customized shelving. Think before buying a delivery truck – $1,500 worth of produce will fit in the back of a Prius! Almost no fuel costs! Daniel also recommends buying an insulated truck body to convert into a cooler. It can double as a screen for crew outdoor movie nights! Don’t forget to have fun!

We have a captive market at Twin Oaks (more politely called direct supply), so I‘m not the best reviewer of information about selling. But the section on their hiring process really grabbed me. “We are not just hiring a pair of hands to meet our labor needs; we are inviting someone into our community, our family, and our home.†Spell out and keep to high standards, provide a social experience, show care and camaraderie, train adequately, and compensate fairly. Interview well, check references, have a working interview (paid) if you can; write out your job offer. Provide guidelines with goals for pace and efficiency. Each person should be able to harvest, wash and pack about $80 worth of produce per hour. Share the joyful observations of life around you.

Daniel describes his recordkeeping, where the plan becomes the record. He recommends Holistic Management by Allan Savory with Jody Butterfield. Define your farms’ purpose, plan the season, plan the week. A plan is just a plan, sometimes plans change. Look for opportunities to record aggregate data, such as recording what you take to market and what you bring back, rather than each individual sale. At the end of the season, add up sales for each crop and divide by the number of beds to calculate the revenue per bed, and the yield of that crop. Having standard sized beds makes this simple. Add into pre-existing records and eliminate multiple versions of the same data. Make one spreadsheet of notes for next year. You can sort it by crop or by month, or by plot number.

Their Plan for the Week is an online spreadsheet accessible to all via a laptop in the barn. (Obviously they have better internet than we do!) Each week has a tab, each day has a column, and each plot has a row with tasks, times and sometimes a name. Once a week, the crew walks the farm and makes the list for each day, including any tasks carried over. Nothing is erased (it becomes a record!) When someone completes a task, they use a strike-through font and add notes. At the end of each day, remaining tasks are reprioritized for the rest of the week. This spreadsheet becomes the farm journal, and is easily searchable.

Frith Farm has a four-year rotation starting with smothering followed by transplanted cucurbits or nightshades and a winter-killed cover crop. The second year involves brassicas followed by root crops, with mulch over-winter. The third year is devoted to repetitions of salad crops, and a winterkilled cover crop. The fourth year is for alliums and an over-wintering cover crop. Consider the crop spacing you need for the new crop, and the spacing of the stubble from the previous crop. You often don’t need a clear bed, just clear rows where you intend to plant.

During the winter they create their attractive crop rotation plan where each plot has 12 rows (for the beds), with “under-rows†(for under-sowing) and 12 columns (for the months). It’s color coded for quick reference. From that rotation plan, they create a Greenhouse Plan and a Seed Order.

Next is a Harvest Plan for each harvest day, starting with walking the fields to take notes, balancing what is mature with what is needed. The evening before, the harvest manager makes a list of crops, quantities, and picking order. Each harvest day has a tab on the online spreadsheet, with a row for each crop. The sheet for that day is posted by the time the crew arrives. In this case, pickers use a pen to indicate who is picking what, when it’s done. People work down the list in order, taking the crops to the wash-pack station. That crew cleans the produce and stores it in a cooler, labeled with its destination.

There is a table of revenue data for 16 top-earning vegetables. (The other 45 crops are not shown.) In terms of revenue per bed, ginger wins at $2442, but it is in place all year (and I think it is in high tunnels). Taking bed-months into account, ginger still wins, but arugula is chasing it. Radishes don’t so well in revenue per bed-season, nor do onions and beets. Frith Farm does not record labor per crop. CSA growers need to provide variety, not just the “most profitable†crops.

Success includes sustainability, considering the people and the planet as well as the profit. Profit can be understood as ability to reinvest. Exactly where the profits end up is important, and to his credit, Daniel includes his 2018 farm revenue and where it went. Of the total $314,000, $120,000 went to the farm crew (an investment in the local community that makes the farm productive); $11,000 to family loan payments. $92,000 went back to the land (infrastructure, seeds and local biomass). $91,000 left the area, for taxes, insurance, fees, tools and equipment, and non-local inputs including the energy bill.

Purchases like plastic mulch, fossil fuels and manufactured equipment are part of a linear process that essentially convert resources to pollution. Strong words, and why not? We need to each face the full effect of our production.

Frith Farm works to increase food access to people in the community who cannot afford the usual prices of healthy food. They accept SNAP and WIC, donations, and offer gleaning groups the chance to help food pantries. They have sliding scale pricing, barter, work trades, and ride shares, all of which they advertise widely.

On the ecological front, their no-till practices are working daily to increase carbon sequestration by increasing organic matter (less than 4% in 2011, over 10% in 2019). A one per cent increase in OM in the top 10†of an acre of soil removes about 8.5 tons of carbon from the atmosphere.